|

Tuesday, 17 October 2023

quote [ "[…] It required some adjustments to ensure a sustainable and healthy company that can serve its community of artists and fans," the company said. ]

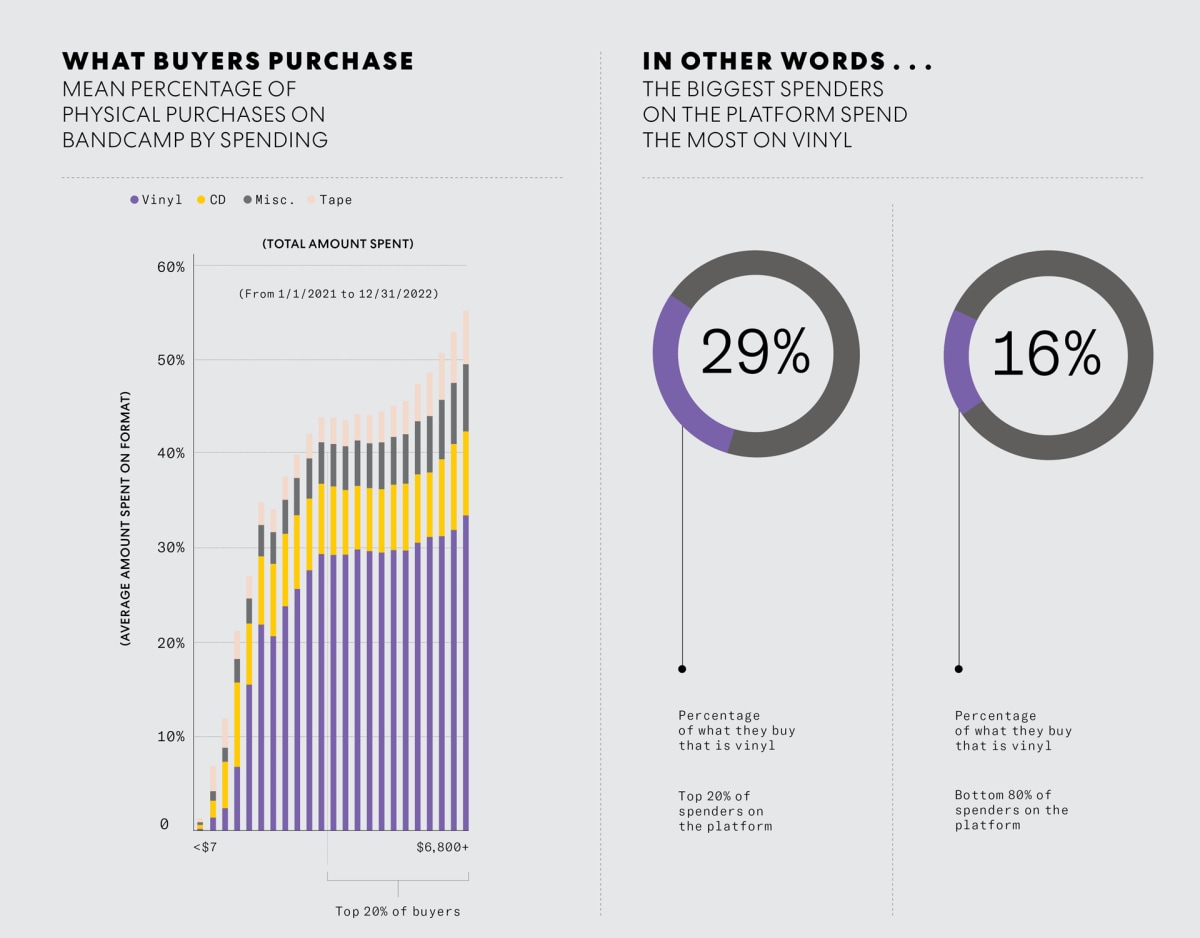

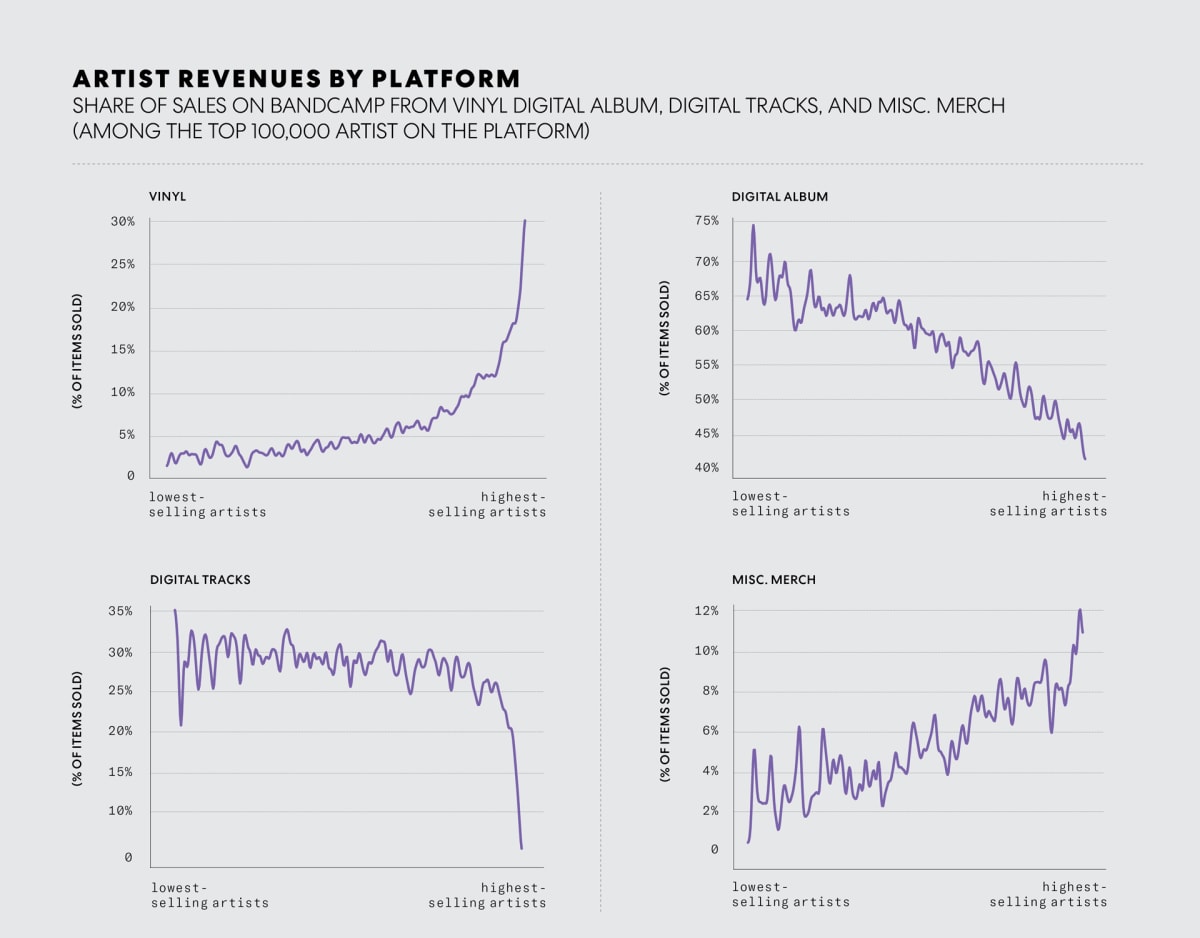

Reveal How Bandcamp makes more money than Spotify Andrew Thompson In the mid-2000s, amid declining revenues from slumping CD sales, the music industry was offered two possible futures. The first was created in 2006 by Daniel Ek, whose new product, Spotify, streamed music from the cloud instantly, as if the music had already been downloaded directly on your device. Users could pay a subscription price—today it’s $10.99—and listen to as much music as they wanted. The second came courtesy of Radiohead with the release of its album, In Rainbows, in 2007. Listeners could pay what they felt was a reasonable amount (the average was $5) to download the album, or they could purchase the physical album as a richly designed disc box including an LP, a bonus CD, and an art book—for $80. Ethan Diamond, an entrepreneur who had created an email platform called Oddpost that got absorbed into Yahoo Mail, turned this model into Bandcamp in 2008, a platform where artists would set their own prices and offer a variety of digital and physical goods, and the company would take a 10% to 15% cut of the sales. Today, one of these companies commands a market cap of more than $26 billion and its app is probably on your phone right now. The other, despite becoming the world’s largest seller of independent music, may evoke little more than vague familiarity. But within this discrepancy lies a paradox: Bandcamp, as comparatively threadbare as it may seem, with about $20 million in net revenue in 2022, is almost certainly profitable—based on the fact that the company has stayed lean and taken on no new funding since 2010. (Bandcamp, which was acquired by Epic Games last year, is now being sold to Songtradr). Spotify, a platform with a mind-bendingly complex bricolage of machine-learning algorithms wrapped in a state-of-the-art UX, has been in the red for 14 of the past 19 quarters since it went public in 2018, and it has not posted a positive quarter since September 2021. In the recent, yet now bygone, days of low-interest rates and growth obsession, Spotify’s lack of profitability was less concerning to the company—fashionable, even. But in an economic environment that’s led recently to bank runs and mass layoffs across the tech industry, it’s worth pondering what success really looks like. For the past three years, as the founder of a research project called Components, I’ve analyzed tens of millions of Bandcamp’s sales, user profiles, and albums and tracks, and I have come to view the differences between these companies in two distinct ways. The first is a fundamental asymmetry in the way people spend on each platform. While Spotify’s customers are capped at paying a maximum of $10.99 per month, the spending of any given Bandcamp customer is theoretically limitless—and affected by nearly endless variables. For example, one of my earlier analyses of the platform found that customers voluntarily paid more money to musicians from their own countries, as well as to those whose releases were associated with charitable causes. Some customers buy one track a year, while others spend thousands of dollars. Jazz listeners are more likely to buy CDs, techno DJs are more likely to buy individual digital tracks, and so on. Bandcamp bakes heterogeneity into its platform in a way that Spotify’s one-size-fits-all service erases. So while Spotify has created a technically complex platform for simple transactions, Bandcamp has created a technically simple platform for complex transactions.  The result is that Bandcamp is able to reap the benefits of what’s known as fat-tailed distributions, in which a minority of individuals comprise the majority of sales—the same logic followed by venture capital firms, whose bets on one or two unicorns make up for all the other portfolio companies that go bust. As I found in a recent analysis, about 20% of Bandcamp customers account for 80% of the site’s total revenues. And within this 20%, the sale of physical goods becomes increasingly important. More than half the objects that the very top spenders buy on the site are physical. And among those objects, vinyl records are more popular than all others (including CDs, tapes, and miscellaneous merch) combined. On average, artists who sell the most physical stuff make the most money on the platform, and among the different kinds of physical stuff they sell, the association is strongest with vinyl. Among the highest-selling artists on the platform, 30% of all the items sold (including all nonmusical merch, like T-shirts) are vinyl records. Among the lowest-selling artists, vinyl was roughly 5%. Downloadable albums and tracks move in the opposite direction, with top-selling artists moving fewer digital goods as they move up in the sales rankings.  Why does vinyl reveal itself as such a disproportionately important channel of spending? The music business at large has suddenly found itself asking the same question. In 2022, LPs and EPs brought in $1.2 billion in revenue, according to the Recording Industry Association of America, the most in Many of the explanations commonly offered for vinyl’s resurgence seem unsatisfactory upon closer scrutiny. Framing the trend as merely a retro craze raises the question of why we haven’t seen a similar spike in 8-tracks and cassettes. Focusing on the collectibility and scarcity of vinyl doesn’t solve the equation either: Both qualities were primary features of NFTs, and we watched the NFT market bottom out the same year that vinyl sales hit their multi-decade record. The most persuasive explanation often cited by vinyl’s advocates is that it’s “tactile.” In using the word, buyers indicate something profoundly important about vinyl’s rise and point to the second reason for Bandcamp’s success and Spotify’s struggles: the value of experience.  The media theorist Marshall McLuhan defined tactility in the 1960s as more than mere physical touch, framing it as “that very interplay of the senses, which we call synesthesia”—the way we see and hear a bird chirp at the same time, or the multisensory operation of driving a car. (To McLuhan, the revolution in electronic media, including television, was largely owed to its ability to convey the sense of existing in an active, multisensory environment by proxy.) When fans call a vinyl record “tactile,” they are implying that streaming is not—or at least it’s less so. While vinyl, with its album art, liner notes, and ritual of being played on a turntable, commands all the senses, Spotify has mostly presented streaming as an ears-only, always-on channel designed to be played in the background from the moment a user wakes up to when they go to bed. While the former presents recorded music in an active, multisensory form, Spotify’s is passive and unisensory. Why does this matter? Because the tactile space is the one where all the stuff we assign irreducible value to—from attending live concerts to sex to playing basketball—resides. And all those examples have what the philosopher John Dewey, one of McLuhan’s most important forebears, referred to as “aesthetic” properties—they are marked by a beginning and an end, cohere into a unifying whole, and reach a consummating moment. The tactile space is where we find meaning, fun, and pleasure regardless of economic conditions. And understanding this is crucial in order to apply the lessons learned from vinyl’s rise to additional parts of the music business (e.g., countries without a strong vinyl tradition and genres that don’t work well with the format) and other industries altogether. Paying $20 for an Imax ticket to Oppenheimer, for example, makes intuitive sense in a way that the same amount paid for a onetime stream on Disney+ wouldn’t. Imax is having a strong year thus far, with revenue up 38% year over year for the first half of 2023. Disney+, meanwhile, has been losing subscribers. The company recently announced that it would be investing $60 billion in more tangible elements of its business, such as theme parks and cruises. Within the tech industry, game studios, which offer users a tactile, finite experience, have made money while startups selling productivity apps—designed to suspend a user in a never-ending state of performative busyness, and wildly plentiful 10 years ago—have all but dried up. Fifteen years of low interest rates allowed Silicon Valley to offer consumers relatively little tactile pleasure. Venture capitalists had enough “easy money” to subsidize companies—like Spotify—built on illogical microeconomics that created products people used because they were free or nearly so, not because they were loved. (Reports of childlike joy emerging from 3D virtual world Decentraland have so far been scant.) Some of these VC-backed companies may survive the downturn because they’ve got leftover cash reserves or funding from a fresh hype. Others might consider embracing a new understanding of economics—and who their customers really are.

|

|

damnit said @ 10:00pm GMT on 17th Oct

It was doing well before Epic bought it. Dumb business move.

|

|

s&m hunter said @ 8:33pm GMT on 22nd Oct

This makes me really, really, fucking sad. bandcamp was the only music service I could agree to use.

|

You must be logged in to comment on posts.

thumb via New Old Stock